All About Finishing

The Chair Doctor of Grand Junction doesn't offer this service anymore, but here is information for you.

Benefits of Finishing or Refinishing

-

Frequently less expensive than buying a new piece of the same quality.

-

Restores the beauty, shine and appeal.

-

Protects and enhances the wood's beauty for generations.

-

Pre-catalyzed lacquer is more moisture, temperature, and scratch resistant than many other finishes, while retaining repairability.

We don't do stripping, refinishing or finishing anymore, sadly. The Chair Doctor is semi-retired and it is just too difficult to lift dining room tables and such.

Info on Different Finishes

Oils

Various oils are sometimes used to finish wood, but they don't protect the wood for beans. Moisture easily penetrates oil finishes, they scratch easily, and in general do a poor job protecting and bringing out the true beauty of wood. Most oils only have a flat sheen. Some oils can be polished (Danish craftsmen have a process that makes oil look really nice) which helps with appearance, but still doesn't help with protecting. Some oils have urethane resins added that make them a teeny bit more resistant to wear. One nice thing that can be said for oils is that they are inexpensive and the do-it-yourselfer can easily apply them and reapply if needed. But we don't recommend them, and you should try to switch them to lacquer whenever you get the chance.

Shellac

This is a very soft finish made from a sort of cocoon generated by a bug called a lac beetle. It can be purchased at the hardware store in a few different colors (usually in flake form), mixes with denatured alcohol in various 'cuts' or concentrations, and is easy to apply. It can also be very beautiful, and is repairable, meaning that frequently scratches and scuffs can be smoothed out with some alcohol or a little more shellac. However, because it is soft, and because alcohol is its solvent (try spilling an alcoholic beverage on it and it will dissolve), it doesn't protect the wood very well or last a long time.

Sometimes a little shellac is used to repair a piece that is already finished with it, but caution is advised.

Polyurethane

The usual finish used by the do-it-yourselfer is polyurethane. It is commonly available in a hardware store, and is a good finish that dries slow so it can be brushed on. It looks good when it's done right, but the problem is it cannot be repaired very well. This is because new polyurethane will only adhere to old polyurethane if the old is cleaned well and scratched with sandpaper. This is called a mechanical bond. Mechanical bonding is okay, but the new polyurethane doesn't blend very well and may peel or flake off over time unless done perfectly. Even then it is a somewhat risky proposition.

Lacquer

Do you remember growing up with mom pestering everyone to use a coaster under our cups? This was because most furniture since World War II was finished with lacquer (although there was some overlap with pieces finished in shellac). Lacquer was developed because there were such large stocks of cotton at the end of the war they didn't know what to do with them. Although it is better than shellac, it is still soft enough to absorb moisture pretty quickly. One downside to lacquer is that the solvents are not good to breath. Another is that lacquer dries so quickly that it is almost impossible to brush it on unless you buy a special, expensive brushing lacquer. But generally finishes look much better sprayed on rather than brushed, anyway.

One of the nice features of lacquer is that it is easily

repaired. New lacquer will melt into old lacquer,

which is what we call a

chemical bond. Because the new lacquer can

(usually) melt into the old stuff, it makes repairs

smoother and more uniform. Most surface scratches

will disappear, and even deep ones can be smoothed over

with a little more work. This reparability feature

of lacquer is one reason why about 90% of commercially

sold furniture since World War II is finished with it.

Pre-Catalyzed Lacquer

In the last 15 years or so, many new finishes have been developed that are even better than regular (nitrocellulose) lacquer, and one of these is pre-catalyzed lacquer. This type of lacquer has a catalyst added to make it harder, which also makes it more moisture, scratch, and temperature resistant than regular lacquer. The nice thing is that it retains the reparability of regular lacquer. Some people compare this product unfavorably to something very hard, such as conversion varnish, but while it is hard it can still be repaired like regular lacquer.

The pictures show a dining table before and after refinishing. It's an eight-foot long solid oak piece with ball and claw pedestal (Just the top was done so the pedestal is not in the pictures). You can see the wear marks from hot stuff, although the finish shouldn't have been this thin to start with.

In the after picture you can see the color is warmed up a little (shifted it from yellow to red) and pre-catalyzed lacquer was applied. Nice result, don't you think?

The Chair Doctor of Grand Junction recommends this finish for table tops and certain other items because of its resistance to wear. Regular lacquer is also good, and sometimes even shellac (although not by preference). Polyurethane is good but not repairable, and the other finishes are just inadequate for daily use.

Epoxy

There

are many types of hard finishes, especially in the

urethane department. Many of them, however, like

polyurethane, are hard to repair. Epoxy combines a hard

finish with reparability, at least in part. Epoxy can be

polished, which removes surface scratches and scuffing.

It can also be coated with lacquer with a chemical bond.

There

are many types of hard finishes, especially in the

urethane department. Many of them, however, like

polyurethane, are hard to repair. Epoxy combines a hard

finish with reparability, at least in part. Epoxy can be

polished, which removes surface scratches and scuffing.

It can also be coated with lacquer with a chemical bond.

These pictures show an old ten foot-long hand-made epoxy covered picnic table that sat on a covered patio for years in Florida. The client was the daughter of the guy who built and finished it, and she wanted it to be restored to something better than the dull, cracked and wrinkled finish that had developed over the years.

She

had a budget, however, and there were deep cracks and

splits where the wood had separated all the way through

the boards (which were very thick by the way). So the

cracks were

filled as well as could be in the time allotted,

and then the top was sanded for quite a while. Two

coats of regular high build lacquer was applied to on the legs and

apron, and three coats on the tops of the table and

benches.

She

had a budget, however, and there were deep cracks and

splits where the wood had separated all the way through

the boards (which were very thick by the way). So the

cracks were

filled as well as could be in the time allotted,

and then the top was sanded for quite a while. Two

coats of regular high build lacquer was applied to on the legs and

apron, and three coats on the tops of the table and

benches.

The picture on the right shows the table top after several coats of the lacquer were applied. The deep areas were epoxy filled by the guy who built it originally. It was not sanded completely smooth within the budget given, but it was smooth enough to slide a napkin across without catching.

Epoxy coatings can also be applied. The surface is very hard, but not weather resistant. But it holds up very well to wear and tear, especially in a restaurant or other commercial situation. Or on picnic tables. The cost for a quarter-inch thick epoxy coating runs about $100.00 a square foot, compared to regular lacquer at about $100.00 per linear foot (for most dining sized tables).

Refurbishing Instead of Refinishing

If your furniture is finished in lacquer (or shellac) it can sometimes be refurbished instead of going through the trouble and expense of stripping and refinishing. By refurbishing we mean that instead of a complete strip and refinish the existing finish is just 'spruced up' using the color and finish that are already present. This is done by coloring any parts of the wood that are marred, cleaning off dirt and applying color to faded areas, then spraying on more lacquer. Sometimes even just lightly applying a little clear lacquer can make a lot of surface scratches go away and restore some color loss (depending on how it was finished to start with). This can be a simple process, or it can rapidly reach a point of diminishing returns (the cost gets too high for the result), where you just might as well go ahead and refinish it.

Shellac can frequently be refurbished by the do-it-yourselfer using denatured alcohol (the solvent for shellac). Surface scratches will usually disappear, and other defects can be smoothed over. However, it can be very tricky to try and refurbish older shellac. Sometimes it develops a white haze that has to be rubbed off with steel wool (4/0 only - never use anything coarser steel wool on furniture) and a steel wool lubricant (a heavy squirt of liquid dish soap in about eight ounces of water will do the trick). Faded color cannot be restored on a shellac finish with alcohol by itself, though. Deep scratches will sometimes disappear from view, sometimes not, but you will still feel them. More shellac can be added, but this can make more problems than it solves because the old shellac is usually pretty dirty, and the newer shellac is much more shiny than the old stuff. If the shellac is wrinkled or cracked (lots of little cracks is called 'crazing') the alcohol won't do much good either (unless you use a LOT of alcohol and risk rubbing through the finish).

It's okay to try it a little on some out of the way spots, but if it gets too involved you might want to just take it to a shop anyway.

Sticky Finishes

Sometimes over time a finish will get sort of sticky (usually this is lacquer). People find this out when they sit on the chair and then can't get up! When they do finally get unstuck, there is a print of their clothes fabric in the finish. The ideal solution is to strip and refinish, but sometimes a budget alternative is desired. What we can do is clean and lightly sand the sticky finish, then apply another coat of lacquer. The new lacquer will chemically bond with the old lacquer and stabilize.

There are several drawbacks to refurbishing. One is that the new finish may peel after a while because it didn't get a real good bond with the old finish. Another is that deep scratches and gouges can still be felt and sometimes seen in the glare of reflected light. A third drawback is that when coloring it is sometimes difficult to get a good color match. Another possible problem is silicone contamination, which causes fish eyes to form in the finish. The lacquer just doesn't stick to silicone at all.

Silicone Oil Contamination

Silicone oil is the bane of refinishing work. It is found in most commercially available products used for dusting. The problem with it is that once it gets into the wood it is impossible to remove. Over time the finish develops small cracks, and the silicone slips into the wood that way. Then when new finish is sprayed on it is possible (and very probable) to get something called 'fish eyes.' A fish eye is where the finish is pushed aside by the silicone in what looks like a little crater or eye of a fish (hence the term 'fish eye'). Finish will not stick to silicone because of reduced surface tension (it's too slick). The only cure for we know of for fish eyes is to sand and lightly reapply finish until it is built up enough to cover the area. This adds expense to the refinishing and is kind of sad because it didn't need to happen in the first place.

There are a couple of tricks that refinishers use to get around the silicone problem. One is to add silicone to the lacquer (yes, it sounds weird, but it works). Another is that it seems to help to color the wood with an oil-based stain (which have mineral spirits for a solvent). Sometimes the contamination isn't too deep and can sort of be sanded out. Or a combination of all of these.

But do yourself a favor and stop using all those dusting products. You don't need them. It doesn't do anything for the finish except put a slight sheen on it (at least until it soaks down into the wood through cracks in the finish) and make it feel slippery. One of the biggest con jobs in marketing today is the job that the manufacturers of these products have done in convincing people that furniture is 'thirsty' and has to be fed. With their expensive product, of course. The thing is, wood will extract the moisture it needs (which isn't much) from the surrounding air. The products containing silicone don't do a thing for 'feeding' wood at all. They just 'feed' on the contents of your wallet. Instead, just use a dry or slightly damp cloth (sprits on a squirt or two of water with a spray bottle). If you want to remove heavier soil, use a little glass cleaner. This will do the same thing as the dusting products in removing dust, and you don't risk contaminating the finish with silicone.

Patina

- (You can read more on the subject of Coloring under the Staining heading too). Most wood that has had a finish on it for a long time has what is referred to as 'patina.' This is a fancy word for 'looks old.' You can think of it as a seasoning of the wood to make it look aged. In the pictures below you can see the effect of patina on the appearance of a rocking chair. The picture on the left is a Lincoln Rocker (circa 1860) with old shellac on it, and the picture on the right is after stripping and with clear lacquer applied. The wood appears to be maple, but there is an aged tone to it that is just beautiful.

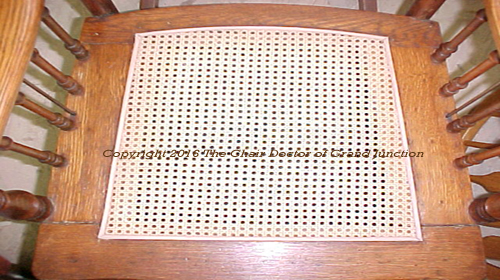

Sanding will mess up the patina. If sanding is started, it has to be done thoroughly, which can be expensive. On the chair above it would be impossible to sand completely because of the cane edges (can't get around all the angles) unless it is sanded before putting the cane on (in the event the cane is being replaced also). Working with the patina instead of against it makes for a much better looking piece, although it can be duplicated using shellac too.

Generally you try to work with the wood's natural color instead of trying to make it look like something it isn't. If you like the beauty of wood, then it takes some skill and time to bring that out. If you don't, then painting always works.

Above is another set of before and after pictures. The one on the left shows a chair that has been weathered and at one time had shellac for a finish. The one on the right is after stripping and thorough sanding (necessary on weathered wood). The chair was disassembled and most of the sanding done while it was apart and before it was re-glued. This makes the edges and corners look nicer. Notice in the before picture there is a missing stretcher between the legs (another stretcher was missing between the back legs). New pieces had to be made, which were made out of red oak (okay for this instance because of the location of the new pieces), then tinted to match the golden color of the quarter-sawn white oak. A medium walnut pigmented oil-based stain was used to color the chair, so the old look (or patina) of quarter-sawn white oak was retained. The pigment helped the 'tiger eyes' of the oak just 'pop' right out.

Colors and Color Matching

There really

are only three colors - Red, Blue, and Yellow.

These are called the primary colors, because all other

colors are based on these three.

Red and yellow

are 'warm' colors, for obvious reasons, while blue is a

'cool' color. These three colors are mixed

together in various proportions to get all the others.

When you try to determine the color you want an

item refinished to, try to decide if a

warm color (orange or traditional maple, golden oak,

yellow oak, etc.) is preferred, or a cool color like

dark walnut. Look at samples of different colors,

but instead of trying to find an exact color (the

samples hardly ever look exactly like your furniture

anyway because of age and grain differences) try to

get an idea of likes and dislikes. Then you can

make a more educated try at the final color, taking into

consideration the specifics of the piece and 'mixing'

that together with your color preferences.

Of course, if you have a sample of a color you like, it is easier to try and match it exactly. Usually you can get very close, if not right on. Again, and this is very important, you can't always get an exact match because of age and differences in grain.

These two pictures show a table that has two colors - a maple interior and black border. This kind of table is harder to refinish because of the differences, especially when you are trying to get the sheen correct. The black shading was part of a toning process applied when the table was new, but had mostly faded except for the leaves. The center part had a runner on it for a while.

The client decided she didn't want the black toner effect this time, nor did she want the fly speck addition, plus she preferred to have the center more brown.

It ended up looking very spectacular.

Rubbing Out or Polishing a Finish

Preparation, choosing and applying the finish is only part of the job. After any finish is sprayed on (or even brushed or wiped) it must be 'rubbed out' for a truly pleasing appearance. No matter how perfect the spray booth, or how perfectly the finish is applied, there are always defects that occur, from the occasional hair to suicidal bugs. This isn't a problem, because in the final polishing process all of these can be eliminated. The result is a soft velvety feeling sheen that glows with just the right amount of diffused light.

Finishes can be rubbed out to a different sheens, such as gloss or satin. This requires a number of stages of wet sanding with very fine sandpaper and steel wool, frequently using just hands but also sometimes using a special (and expensive) sander called a finish sander.

There are three basic sheens to a finish - flat, satin or semi-gloss, and gloss. Most people are familiar with these, but to summarize the differences a flat sheen has almost no light reflection, a satin has some, and a gloss has a lot of ability to reflect light clearly.

All sheens are made by scratching. A flat sheen has large scratches that break up light and cause it to look blurry or 'diffused.' A satin sheen has smaller scratches, and a gloss sheen, even if it doesn't look like it, has very small scratches. The scratches on a gloss sheen are just so small that they don't break up light like the larger scratches in the other two sheens.

In the picture, half of the maple drop-leaf table is gloss (left half) and half is satin. The line is right down the middle of Bruce's reflection. Look at the glare from the lights and you can see that on the right the light (about an inch below the 'r' in Doctor) is a little more diffuse (satin), while on the left (just off the shoulder of the shadow below the 'o' in the word 'of') the light reflection is less diffuse or sharper (gloss). You can also see that the reflection of Bruce's hand (his right, your left) is clearer than the other one. Depending on the resolution of your screen, you might even be able to see the difference without trying too hard.

Gloss finishes are more expensive than either satin or flat for several reasons. One is that every tiny little defect shows up, so all of them have to be removed. Two is that extra rubbing and polishing is needed to raise the sheen to a gloss. If a very smooth (filled-pore or 'no grain') appearance is desired, that requires pore fillers and other work and is even more expensive. Pianos, for instance, can cost up to $1,000.00 a foot (a 9 foot concert grand can cost about $9,000.00 as of 2010 to refinish this way) because of the amount of work involved in refinishing.

Staining

There are basically two types of stain - pigmented and dye. Pigmented stain has little bits of, well, dirt in it to make the color. Dye is clear (no pigment). Some people think that pigment obscures the grain, which is partially true. But we happen to think that the pigments help enhance the depth of the finished work and help to bring out contrasts in the grain. It also seems to be more compatible with the patina of older wood. Dyes make for a more clear and even look, but they can also obscure the wood if they are in high concentration.

On older wood, with differences in piece colors (like for instance cherry, which has a wide variation between white and dark red) pigmented stains help to even out the differences. So do dyes, if you put them directly in the lacquer, but can get too dark very quickly and they are a little more difficult to control. A lot of older furniture was stained using aniline dyes. We use both pigmented and dye stains, depending on the age of the wood, the design of the furniture, and other factors like whether or not all the color could be removed in the stripping process (see the section on Stripping and Sanding).

The next three pictures show matching cherry end tables. The one on the left has been refinished already, the one on the right is original. Color on the left was imparted through a dark mahogany oil stain. Even though this is a pigmented stain, the grain seems to just 'pop' out, bringing out more of the beautiful cherry color. A little bit of cherry dye stain was added after the first coat of gloss pre-cat lacquer to shift the color more to the red side.

Below is a close up of the top of both tables, illustrating the difference between the coloring (and sealing). The original (still right side) finish and color just seems to obscure more of the wood grain than we prefer.

Below is a third shot of the tops of the cherry tables, original still on the right, but without a flash. This is a little closer to what the eye naturally sees as opposed to the pictures above which used a flash. Notice how the grain just seems much more well defined on the refinished table (left) and more obscured on the original (right). The color is also much more even than on the original. The white marks on the original are dings and scratches.

Dyes can help even out the 'blotchiness' of a piece, like maple. However, blotchiness is the natural tendency of some wood, and can be very attractive if managed properly. When the color gets too even it tends to look like paint. If the color is applied directly to the wood, blotchiness is more likely. If instead you put the dye in the sprayed-on lacquer, you can do what's called 'toning.' Lacquer with the dye in it helps to sneak up on the color that you want (hopefully without shooting right past it and making it too dark) if applied skillfully. The drawback to toning is that if later the finish is chipped or scrapped off, the wood color underneath shows right through. This can also happen if you apply the color directly to the wood, but it has to be a pretty deep scrap to get past the color.

The Chair Doctor of Grand Junction recommends both types of stain to color wood, depending on the desired result. We prefer the appearance of pigmented stains for most projects, but we've used toning quite extensively also, especially when touching up or patching a finish.

What Kind of Wood?

Identifying wood types is not as easy as you'd think.

Only that Al Borlund character on the old Home Improvement TV show could do it by smell.

Some people will try to convince you that they can tell what wood your furniture is made out of just by looking. This, as they say, is horse-hockey. A few of the basic types can be identified by looking, such as oak or maybe the difference between white and red oak. However, few people (even us) can tell exactly what kind of oak it is. There are about 86 types of oak in North America alone, and many species of wood world-wide resemble each other to a certain extent.

We can (usually) identify teak, white oak as opposed to red oak, quarter-sawn oak (usually white), maple (in this country there is hard maple which includes sugar and black maple, as well as soft maple which includes silver and and red, although curly, bird's eye, quilted and fiddle back figuring are pretty distinct), cherry (most of the time), some types of mahogany, walnut and pine. But if you ask us what kind of walnut or mahogany, for instance, we couldn't necessarily tell you (and very few people, if any, can, except maybe the Al Borlund character on Home Improvement). It is also very hard to tell the difference between wood such as pecan and hickory, and while the difference between white ash and black ash is more obvious, trying to figure out if the wood is ash in the first place can be problematic.

Oddly enough, like Al Borlund, we can sometimes use smell to help identify wood (and sometimes even to tell if it's very old or not), and there are some chemical tests that are available. Of course, most of the time it isn't really necessary to spend a lot of money trying to figure out exactly what wood your furniture is made of. Our glues work on all sorts of wood, and refinishing is expensive enough without adding specialized treatments for specific woods.